El Niño & La Niña

What is El Niño?

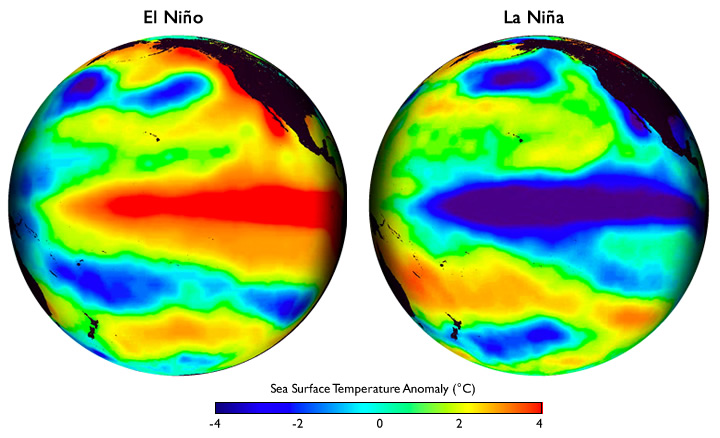

El Niño is a warming of the Pacific Ocean between South America and the Date Line, centered directly on the Equator, and typically extending several degrees of latitude to either side of the equator. Coastal waters near Peru also warm. The warming is expressed as a departure from long-term average ocean temperatures, which are generally cool in the region, due to upwelling. El Niño is thus associated with a slackening, or even cessation, of the cold upwelling conditions which typically prevail in that area.

During a typical El Niño, the ocean warms a degree or two (C) above its climatological average. A strong El Niño can warm by 3-4 degrees C over large areas, and even 5 degrees C in smaller regions.

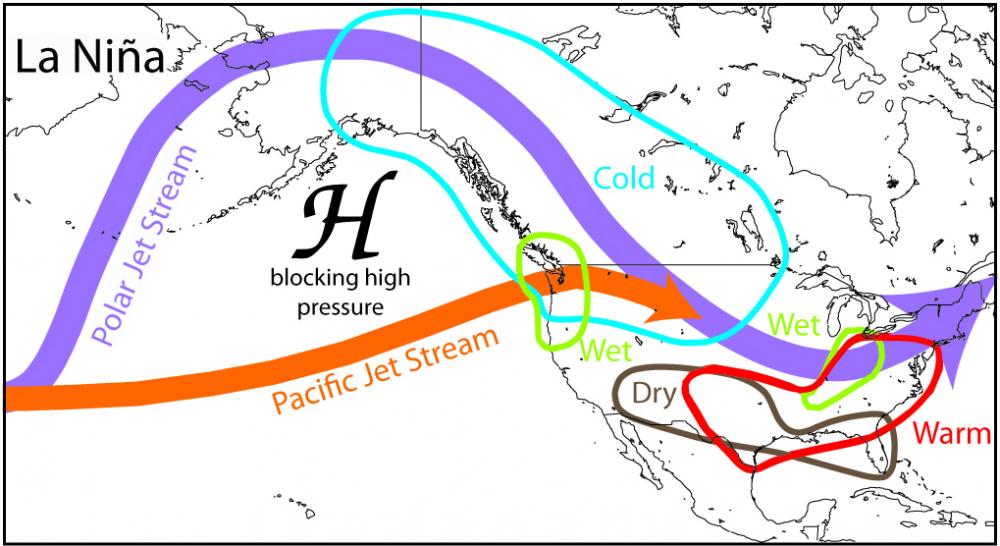

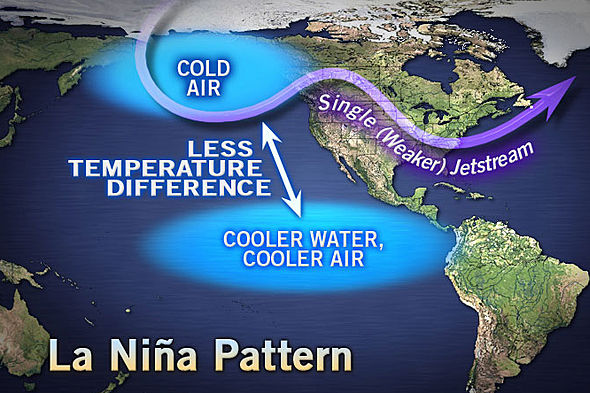

What is La Niña?

La Niña is essentially the opposite of El Niño. La Niña exists when cooler than usual ocean temperatures occur on the equator between South America and the Date Line. The name La Niña ("the girl child") was coined to deliberately represent the opposite of El Niño ("the boy child"). The terms El Viejo and anti-El Niño are also sometimes used. La Niña occurs almost as often as El Niño, but has been lesser known. La Niña and El Niño are but two faces of the same larger phenomenon.

Stronger than usual trade winds accompany La Niña. These winds, from the east, push the ocean water away from the equator in each hemisphere. (This is caused by the rotation of the earth.) Cold water from below rises to replace the warm surface water which has moved away from the equator.

The cool water acts as an impediment to the formation of clouds and tropical thunderstorms in the overlying air. This suppression of rain-producing clouds leads to dry conditions on the equator in the Pacific Ocean from the Date Line east to South America.

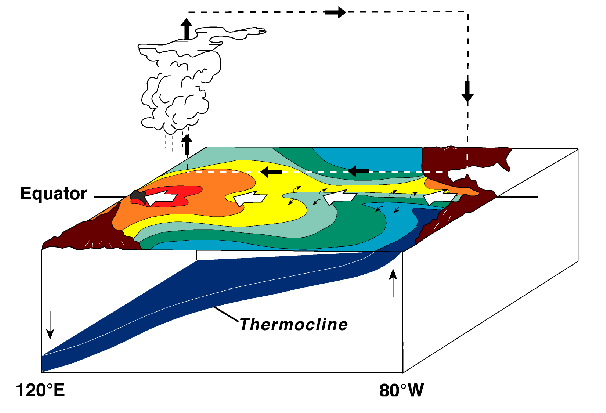

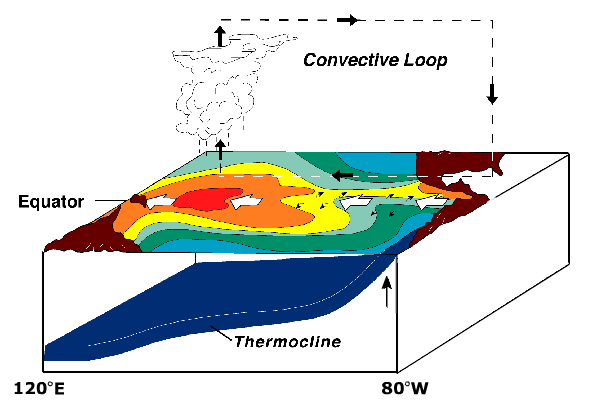

Normal (Long-term Average) Conditions

The colored areas on the top of the block diagram portion denotes sea surface temperatures (SST) during normal conditions. The red colored area in the western Pacific basin (120°E) denotes the highest SST. These highest SST occur under [(considerable cloudiness) (clear skies)] in the tropical Pacific. This SST pattern is caused by relatively strong trade winds pushing sun-warmed surface water westward, as indicated by the direction of surface currents.

Warm surface water transported by the wind away from South America coast (80°W) is replace by cold water rising from below in a process called upwelling. Upwelling of cold deep water results in relatively [(high) (low)] SST in the eastern Pacific basin (80°W) compared to the western Pacific basin (120°E).

(NOAA / PMEL / TAO)

Tropical Pacific During El Niño

Compared to normal (long-term average conditions), the area of stormy weather during El Niño has moved [(eastward) (westward)]. While no two El Niño episodes are exactly alike, all of them exhibit most of the characteristics shown in the El Niño schematic.

In response to changes in surfaces currents, sea surface heights in the eastern tropical Pacific basin (80°W) are higher than during normal conditions. At this time, the arrival of the warmer water in the east causes the surface warm-water layer to thicken. Evidence of this is the [(shallower) (deeper)] depth of the thermocline to the east compared with normal conditions.

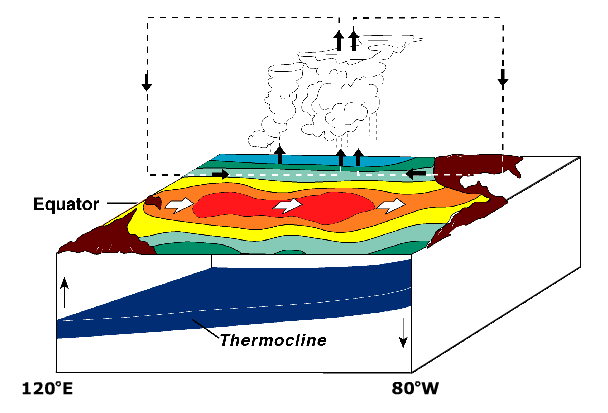

Tropical Pacific During La Niña

At times the tropical Pacific experiences trade winds that are stronger than normal conditions with SST lower than usual in the eastern tropical Pacific basin (80°W) and higher than usual in the western tropical Pacific basin (120°E). Because stronger trade winds produce stronger surface currents during La Niña, the warm water is pushed westward and colder water wells up to cause below-average sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific basin (80°W). It also follows that sea surface temperature in the western tropical Pacific basin (120°E) must be [(above) (below)] its normal condition average.